Abstract

Review Article

Management and use of Ash in Britain from the Prehistoric to the Present: Some implications for its Preservation

Jim Pratt*

Published: 23 January, 2024 | Volume 8 - Issue 1 | Pages: 001-011

The properties that make the wood of fast-grown Ash pliable, strong, and resilient have been exploited by man for thousands of years, and are illustrated by reference to the probable use of Ash timber for tools, arms, and transport by the Roman Army of Occupation in Britain two thousand years ago. Militarily organized and disciplined, the Roman Army was responsible for changing the face of Britain with huge infrastructure projects that required significant numbers of tools, equipment, and fuel, in addition to the arms it used to maintain control over the fractious tribes of the north. The extent to which it maintained supplies of this valuable resource by managing its woods, possibly by coppicing, is discussed and raises the question as to the degree of genetic selection involved in coppicing.

Ash: Fraxinus excelsior: extinction: prehistoric and historic uses: Roman army military use of Ash.

Read Full Article HTML DOI: 10.29328/journal.acee.1001059 Cite this Article Read Full Article PDF

References

- Maigrot Neolithic polished stone axes and hafting systems: technical use and social function at the Neolithic lakeside settlements of Chalain and Clairvaux. In: Davis and Edmonds (eds.) Stone Axe Studies III. Oxbow Books, Oxford. 2011; 441.

- Mytting Norwegian Wood. Chopping, Stacking and Drying Wood the Norwegian Way. MacLehouse Press, London. 2015; 192.

- Green HS. Late Bronze Age wooden hafts from Llyn Fawr and Penwyllt and a review of the evidence for the selection of wood for tool and weapon handles in Neolithic and Bronze Age Britain and Ireland. Bull. Board of Celtic Studies. 1978; 28: 136-141.

- Harding A, Young Reconstruction of the hafting methods and function of stone implements. In McK Clough and Cummins (eds.) CBA Research Report No 23: Stone Axe Studies. Council for British Archaeology, Lond. 1979; 137.

- Sheridan Scottish stone axeheads; some new work and recent discoveries. In Sharples and Sheridan (eds.) Vessels for the Ancestors: Neolithic of Britain and Ireland. EUP, Edinburgh. 1992; 416.

- Cooney G, Mandal The Irish Stone Axe Project, Monograph 1. Wordwell Ltd, Bray, Ireland. 1998; 220.

- Dinnis R, Stringer Britain: one million years of the human story. Natural History Museum, London. 2014; 152.

- Thieme Lower Paleolithic hunting spears from Germany. Nature. 1997; 385: 807-810.

- Brazier The Timbers of Farm Woodland Trees. Bulletin, Forestry Commission No 91, HMSO, Lond. 1990; 8.

- Desch HE, Dinwoodie Timber: structure, properties, conversion and use. Palgrave Macmillan. 1996; 306.

- Cook J, Gordon A mechanism for the control of crack propagation in all brittle systems. Proc Royal Soc A. 1964; 282: 508.

- Rackham O. The Ash Tree. Little Toller Books, Dorset. 2014; 178.

- Penn The Man who Made Things out of Trees. Particular Books, 2015; 234.

- Evans Silviculture of Broadleaved Woodland. Forestry Commission Bulletin 62. H.M.S.O. Lond. 1984; 232.

- Hiley A Forestry Venture. Faber and Faber, Lond. 1964; 240.

- Rackham Neolithic woodland management in the Somerset levels: Gavin’s, Walton Heath and Rowland’s tracks. In Coles et al (eds.) Somerset Levels Project No. 3. 1977; 65–72.

- Milner N, Taylor B, Conneller C, Schadia-Hall Star Carr. Life in Britain after the Ice Age. Council for British Archaeology, York. 2013; 112.

- Catling Bouldnor Cliff: a glimpse into the Mesolithic. Current Archaeology. 2012; 262: 31-37.

- Coles An experiment with stone axes. Pages 106-107 in: McK Clough and Cummins (eds.) CBA Research Report No 23: Stone Axe Studies. Council for British Archaeology, Lond. 1979; 137.

- Jacomet S, Leuzinger U, Schibler J. The Neolithic lakeside settlement of Arbon, Bleiche 3. Environment and economy. Reprint synthesis from archeology in Thurgau 12. Frauenfeld. 2004.

- Dumayne-Peaty L, Barber Archaeological and environmental evidence for Roman impact on vegetation near Carlisle, Cumbria: a comment on McCarthy. The Holocene. 1997; 7(2): 243-246.

- McCarthy Woodland and Roman Forts. Britannia. 1986; 17: 339-343.

- Rackham The history of the countryside. Dent, London. 1986; 445.

- Coles Wood species for wooden Figures: a glimpse of a pattern. In: Gibson and Simpson (eds.) Prehistoric Ritual and Religion: Essays in honour of Aubry Burl. Sutton Publishing. 1998.

- Coles JM, Orme Prehistory of the Somerset Levels. Somerset Levels Project 1980. 1982; 64.

- Thomas Biological Flora of the British Isles: Fraxinus excelsior. Journal of Ecology in press. 2016; 2745.12566.

- Brondsted The Vikings. (trans. E. Bannister-Good.) Penguin Books, Lond. 1960; 320.

- Frazer The Golden Bough. Macmillan, Lond. 1949; 756.

- Margary Roman Roads in Britain. John Baker, Lond. 1967; 546.

- Webster The Roman Imperial Army of the first and second centuries AD. Adam and Charles Black, Lond. 1969; 330.

- Wacher The towns of Roman Britain. Batsford. 1974; 460.

- Peddie J. Conquest: the Roman invasion of Britain. Sutton Publishing, Glos. 1987; 214.

- Bishop The secret history of the Roman roads of Britain. Pen and Sword Military, Barnsley. 2014; 210.

- Cunliffe Iron Age Britain. Batsford, Lond. 1995; 128.

- Millett How Roman occupation redrew an iron-age landscape. Current Archaeology. 2016; 314: 26- 31.

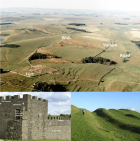

- Breeze The Northern frontier of Roman Britain. Batsford, Lond. 1982; 188.

- Curle A Roman Frontier Post and its People. Maclehose, Glasgow. Vols I and II. 1911.

- Bishop MC, Coulston Roman Military Equipment, 2nd Edition. Oxbow, Oxford. 2013; 322.

- Webster The Roman Army: An Illustrated Study. Grosvenor Museum, Chester. 1956; 52.

- Coles JM, Heal SVE, Orme BJ. The use and character of wood in prehistoric Britain and Ireland. Proc Prehistoric 1978; 44: 1-45.

- Travis H, Travis Roman Shields. Amberley Publishing, Stroud. 192. Vegetius PFl. Epitoma rei militaris. II, 11. 2014; 192.

- Bishop The Gladius. Pers Comm. 2016.

- Pitassi M. The Roman Navy. Seaforth. 2012; 184.

- Nash-Williams The Roman frontier in Wales. University of Wales Press, Cardiff. 1969; 206.

- Hanson The organisation of Roman military timber supply. Britannia. 1978; 9: 293-305.

- Shirley Building a Roman legionary fortress. Tempus. 2001; 160.

- Richmond Roman Timber Building. In Jope (ed.) Studies in Building History. Odhams, Lond. 1961; 287.

- Hanson Elginhaugh: a Flavian fort and its annex. Britannia Monograph Series No. 23, S.P.R.S., London. 2007; 686.

- Dumayne-Peaty L, Barber K. Late Holocene vegetational history, human impact and pollen representivity variations in northern Cumbria, Journal of Quarternary Science. 1998; 13(2): 147-164.

- Tipping Medieval woodland history from the Scottish Southern Uplands. In Smout (ed.) Scottish Woodland History. Edinburgh. 1997; 215.

- Breeze DJ, Dobson B. Hadrian’s Wall. Allen Lane. 1976; 324.

- Hill P. The construction of Hadrian’s Wall. Tempus. 2006; 160.

- Moffat The Wall: Rome’s greatest frontier. Berlinn, Edinburgh. 2009; 270.

- Crouwel Chariots and other wheeled vehicles in Italy before the Roman Empire. Oxbow, Oxford. 2012; 234.

- Carter S, Hunter F, Smith A 5th Century BC Iron Age Chariot Burial from Newbridge, Edinburgh. Proc. Prehistoric Society. 2010; 76: 31-74.

- Jenkins Traditional Country Craftsmen. Routledge & Kegan Paul, Lond. 1966; 236.

- Anon Utilisation of Hazel Bulletin No 27, Forestry Commission, HMSO, Lond. 1956; 34.

- Rawling The Barn. In Slater and Rawling (eds.) How Hall: Poems and memories, a passion for Ennerdale. Lamplugh and District Heritage Society, 2009; 90.

- Stevens WC, Turner N. Woodbending Handbook. HMSO. 1970; 109.

Figures:

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

Figure 8

Figure 9

Figure 10

Figure 11

Figure 12

Figure 13

Figure 14

Similar Articles

-

Removal of Chromium from Aqueous Solution by Thermally Treated Mgal Layered Double HydroxideDashkhuu Khasbaatar*,Enkhtur Otgonjargal,Byambasuren Nyamsuren,Enkhtuul Surenjav,Gunchin Burmaa,Jadambaa Temuujin. Removal of Chromium from Aqueous Solution by Thermally Treated Mgal Layered Double Hydroxide. . 2017 doi: 10.29328/journal.acee.1001001; 1: 001-008

-

Thermal Stress Analysis of a Continuous Rigid Frame BridgeYafei Xu*,Shiwei Ge,Xiao Zhou,Shangyu Peng. Thermal Stress Analysis of a Continuous Rigid Frame Bridge. . 2017 doi: 10.29328/journal.acee.1001002; 1: 009-019

-

Wave Forces on Vertical Structures in Shallow Water: Numerical EvaluationFabio Dentale*,Ferdinando Reale,Angela Di Leo,Eugenio Pugliese Carratelli,Marina Monaco. Wave Forces on Vertical Structures in Shallow Water: Numerical Evaluation. . 2017 doi: 10.29328/journal.acee.1001003; 1: 020-033

-

A Preliminary Laboratory Investigation of Methane Generation Potential from Brewery Wastewater using UASB ReactorMA Karim*,Benjamin L Moss. A Preliminary Laboratory Investigation of Methane Generation Potential from Brewery Wastewater using UASB Reactor. . 2017 doi: 10.29328/journal.acee.1001004; 1: 034-041

-

Hydraulic jump experiment in a rectangular open channel flumeMostafa M El-Seddik*. Hydraulic jump experiment in a rectangular open channel flume. . 2017 doi: 10.29328/journal.acee.1001005; 1: 042-048

-

Natural and effective ways of purifying lake waterSavita Dixit*,Swapnil Lokhande. Natural and effective ways of purifying lake water. . 2017 doi: 10.29328/journal.acee.1001006; 1: 049-054

-

Rapid Microbial Growth in Reusable Drinking Water BottlesQishan Liu*,Hongjun Liu. Rapid Microbial Growth in Reusable Drinking Water Bottles. . 2017 doi: 10.29328/journal.acee.1001007; 1: 055-062

-

Cumulative Effect Assessment: preliminary evaluation for Environmental Impact Assessment procedure and for environmental damage estimationMarco Ostoich*,Andrea Wolf. Cumulative Effect Assessment: preliminary evaluation for Environmental Impact Assessment procedure and for environmental damage estimation. . 2017 doi: 10.29328/journal.acee.1001008; 1: 063-090

-

Automatic control and protection of Coal Conveyor System using PICDhamodharan K*,Mumtaj S,Hari Prasad K,Kamesh Gautham B. Automatic control and protection of Coal Conveyor System using PIC. . 2018 doi: 10.29328/journal.acee.1001009; 2: 001-005

-

Use of Geosynthetic materials in solid waste landfill design: A review of geosynthetic related stability issuesMA Karim*,Lin Zhao. Use of Geosynthetic materials in solid waste landfill design: A review of geosynthetic related stability issues. . 2018 doi: 10.29328/journal.acee.1001010; 2: 006-015

Recently Viewed

-

A Low-cost High-throughput Targeted Sequencing for the Accurate Detection of Respiratory Tract PathogenChangyan Ju, Chengbosen Zhou, Zhezhi Deng, Jingwei Gao, Weizhao Jiang, Hanbing Zeng, Haiwei Huang, Yongxiang Duan, David X Deng*. A Low-cost High-throughput Targeted Sequencing for the Accurate Detection of Respiratory Tract Pathogen. Int J Clin Virol. 2024: doi: 10.29328/journal.ijcv.1001056; 8: 001-007

-

A Comparative Study of Metoprolol and Amlodipine on Mortality, Disability and Complication in Acute StrokeJayantee Kalita*,Dhiraj Kumar,Nagendra B Gutti,Sandeep K Gupta,Anadi Mishra,Vivek Singh. A Comparative Study of Metoprolol and Amlodipine on Mortality, Disability and Complication in Acute Stroke. J Neurosci Neurol Disord. 2025: doi: 10.29328/journal.jnnd.1001108; 9: 039-045

-

Development of qualitative GC MS method for simultaneous identification of PM-CCM a modified illicit drugs preparation and its modern-day application in drug-facilitated crimesBhagat Singh*,Satish R Nailkar,Chetansen A Bhadkambekar,Suneel Prajapati,Sukhminder Kaur. Development of qualitative GC MS method for simultaneous identification of PM-CCM a modified illicit drugs preparation and its modern-day application in drug-facilitated crimes. J Forensic Sci Res. 2023: doi: 10.29328/journal.jfsr.1001043; 7: 004-010

-

A Gateway to Metal Resistance: Bacterial Response to Heavy Metal Toxicity in the Biological EnvironmentLoai Aljerf*,Nuha AlMasri. A Gateway to Metal Resistance: Bacterial Response to Heavy Metal Toxicity in the Biological Environment. Ann Adv Chem. 2018: doi: 10.29328/journal.aac.1001012; 2: 032-044

-

Obesity in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease as a Separate Clinical PhenotypeDaria A Prokonich*, Tatiana V Saprina, Ekaterina B Bukreeva. Obesity in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease as a Separate Clinical Phenotype. J Pulmonol Respir Res. 2024: doi: 10.29328/journal.jprr.1001060; 8: 053-055

Most Viewed

-

Evaluation of Biostimulants Based on Recovered Protein Hydrolysates from Animal By-products as Plant Growth EnhancersH Pérez-Aguilar*, M Lacruz-Asaro, F Arán-Ais. Evaluation of Biostimulants Based on Recovered Protein Hydrolysates from Animal By-products as Plant Growth Enhancers. J Plant Sci Phytopathol. 2023 doi: 10.29328/journal.jpsp.1001104; 7: 042-047

-

Sinonasal Myxoma Extending into the Orbit in a 4-Year Old: A Case PresentationJulian A Purrinos*, Ramzi Younis. Sinonasal Myxoma Extending into the Orbit in a 4-Year Old: A Case Presentation. Arch Case Rep. 2024 doi: 10.29328/journal.acr.1001099; 8: 075-077

-

Feasibility study of magnetic sensing for detecting single-neuron action potentialsDenis Tonini,Kai Wu,Renata Saha,Jian-Ping Wang*. Feasibility study of magnetic sensing for detecting single-neuron action potentials. Ann Biomed Sci Eng. 2022 doi: 10.29328/journal.abse.1001018; 6: 019-029

-

Pediatric Dysgerminoma: Unveiling a Rare Ovarian TumorFaten Limaiem*, Khalil Saffar, Ahmed Halouani. Pediatric Dysgerminoma: Unveiling a Rare Ovarian Tumor. Arch Case Rep. 2024 doi: 10.29328/journal.acr.1001087; 8: 010-013

-

Physical activity can change the physiological and psychological circumstances during COVID-19 pandemic: A narrative reviewKhashayar Maroufi*. Physical activity can change the physiological and psychological circumstances during COVID-19 pandemic: A narrative review. J Sports Med Ther. 2021 doi: 10.29328/journal.jsmt.1001051; 6: 001-007

HSPI: We're glad you're here. Please click "create a new Query" if you are a new visitor to our website and need further information from us.

If you are already a member of our network and need to keep track of any developments regarding a question you have already submitted, click "take me to my Query."